The so-called culture wars are not just about race and gender. They encompass a barrage of attacks on progressive or “woke” values to distract attention from catastrophic pandemic management in both Washington and Westminster. On closer inspection, some of the targets in the crosshairs are actually rather conservative; a case in point being the rule of law.

If the prime minister and the home and defence secretaries are anything to go by, lawyers are the new enemies of the state. But as these ministers are not averse to employing briefs in their own causes – both personal and political – I rather suspect it’s the message, not the messengers, that they are trying to destroy.

It is now well over a decade since former master of the rolls Tom Bingham published his seminal book The Rule of Law. The most glittering legal and judicial career notwithstanding, he wanted to make this vital constitutional principle more readily accessible to the people it is designed to protect. He asked me to endorse his book and chair his discussion of it at the Royal Society for Arts. The greatest jurist of my lifetime was also incredibly good at plain English. He set out eight tests for the rule of law with a succinct clarity that any pundit or politician would envy.

Bingham’s third rule was that “the laws of the land should apply equally to all” . His fifth was, “the law must afford adequate protection of fundamental human rights”. At the time, we thought the former incontrovertible and the latter slightly contentious. Ten years on, both values are in peril.

Two bills currently before the House of Commons would undermine these principles. The overseas operations bill would make it much harder to prosecute British personnel for serious crimes – including torture – overseas, and immunise the Ministry of Defence from claims by the very veterans it has neglected.

The second, the covert human intelligence sources (criminal conduct) bill, is arguably even more abhorrent. It grants a host of state agencies the power to licence its agents and officers to commit grave crimes in advance, even here in the United Kingdom.

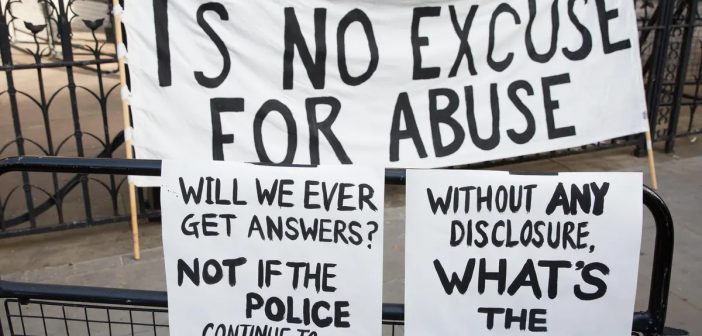

To be clear, I believe many undercover operations to be essential. Yet it was always ridiculous that, while judicial warrants were required for the searches of premises, they were not needed for the far more intrusive and dangerous placing of spies in people’s homes, offices, trades unions, friendship circles and even bedrooms. These remain a matter of administrate discretion for security services, police forces and a host of other state agencies, without the need for any external authorisation.

That’s why Labour changed its policy, a few years ago, to require judicial warrants for the use of undercover officers and spies. Sadly, such an amendment is completely outside the scope of the current “spycops bill”. Instead, the drastic if limited scope of the measure before the Commons on Thursday is confined to licensing criminal conduct.

The argument goes like this. If you are undercover in a terrorist cell, you clearly commit the crime of being in a banned group; if you are spying on drug dealers, you might have to deal, and so on. I completely understand. But our law already requires that any prosecution be in the public interest – and is there a single example of rogue prosecutors going after police officers or MI5 agents for minor crimes necessarily committed in the course of their duty to keep the public safe?

And how much greater will be the temptation to act as instigator rather than observer for undercover operatives given the all-clear to commit even serious criminal offences in the fight against “domestic extremism”, whatever that means in these new, terrifying times?

Imagine a not too distant future where an ever more urgent climate protection movement, that has long since become an irritant of rightwing government, is tempted to stray from its long-standing noble and peaceful path. If this criminal conduct bill passes, how will we ever know if the agitator who took this step was, in fact, an undercover agent?

A culture war where lawyers are traitors – and soldiers and spies beyond the law, no matter what – is thoroughly undemocratic, unBritish and contrary to the rule of law. It’s been tried elsewhere before, and it never ends well.

• Lady Chakrabarti was shadow attorney general for England and Wales from 2016 to 2020, and director of Liberty from 2003 to 2016.

The Guardian.