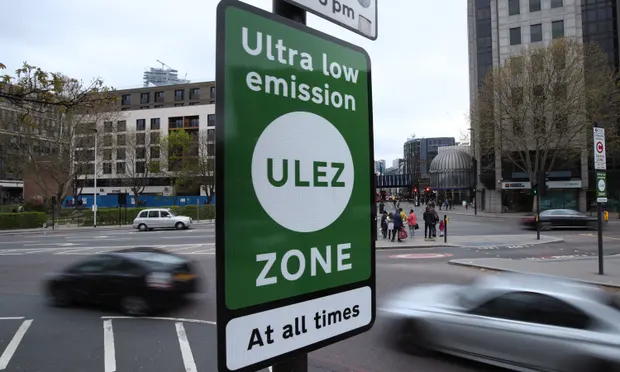

t’s just about possible to see how Sadiq Khan miscalculated so badly when he proposed extending London’s Ultra Low Emissions Zone (Ulez) to cover just about all of the city he presides over. The scheme, which charges older, more polluting vehicles £12.50 a day to drive within its perimeters, had proven relatively uncontroversial when it was limited to the city centre. And the idea sounds nice. The aim is to improve air quality, accelerate the transition to carbon neutral transport, and make the city a more pleasant place to live.

But London is not populated entirely by cycling singletons, who buy all their groceries from the local delicatessen. And now the suburbs are in open revolt. The Ulez extension could not only deny Labour victory in the upcoming Uxbridge by-election, but may even end Khan’s misrule as the capital’s mayor for good.

One reason the scheme met with such little resistance in inner London was that it arguably made less of an impact; public transport is reasonable and fewer people are reliant on cars to get around. Some might have had to sell their vehicles. But the state of congestion in central London, and the proliferation of cycle lanes and 20mph zones, has already dissuaded many from driving.

Outer London is a completely different story. Its population is older. Pensioners are, for obvious reasons, far less likely to be able to shift to alternative modes of transport, while they may be more likely to own relatively elderly vehicles they will have to sell so as not to be hit by the charge. There are more families, who are similarly more dependent on cars. London is also not the universally wealthy city of some people’s imagination. The suburbs may be leafy in parts, but in swathes of the capital, the cost of replacing a car will be debilitating, particularly for the poor.

That is not even to mention the tradesmen, small business owners, and others who rely on vehicles for their work. Earlier in the year, David Lammy, the Labour MP, glibly suggested that plumbers should jump on the Tube instead. How are they meant to do that with all their tools in tow? In any case, public transport in the capital generally runs from the centre to the outskirts. There are relatively few links between the different parts of suburbia, apart from a dysfunctional and unpleasant bus network.

Little wonder, then, that Khan’s plan has sparked a rebellion that the Tories are attempting to exploit. The Labour candidate in Uxbridge has even felt the need to come out in opposition to the mayor’s flagship policy, while Keir Starmer hardly sounds enthusiastic.

Ulez expansion may be crushed by the courts; five councils have brought a legal challenge against the expansion. But the Government should never have allowed Khan to propose it in the first place, not least because a great many of the people who will be affected – those who live just outside Greater London, but who travel in for work, to shop, or see family and friends – cannot even vote to get rid of him.

The London Tories look set to run in the next mayoral elections on a single-issue platform of cancelling Ulez. Many analysts have already written them off, given the woeful state of the party nationally, but they are ignoring that the election will be run for the first time on first-past-the-post. They don’t need to secure a majority of votes. And some think that galvanising the furious minority who loathe Ulez expansion could be enough to force Khan out.

If so, it would arguably be Britain’s first real anti-green citizens’ revolt. There have been flickerings of similar protests in cities like Cambridge, which is contemplating its own demented anti-car schemes. The same is true of similarly poorly-thought proposals in Oxford and Manchester.

Political opposition to extreme green policies is growing right across Europe. In Germany, a row over the compulsory introduction of heat pumps is sinking the Green party and may well finish Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s precarious coalition. In the Netherlands, restrictions on fertilisers and the seizure of agricultural land to secure “biodiversity” is propelling the Farmers-Citizen Movement in the polls.

While Left-wing politicians like Sadiq Khan might dismiss these groups as “populists”, they are tapping into a deep sense of unfairness at policies imposed by an elite to the material detriment of ordinary people. Soon, they may be impossible to ignore.