It’s not hard to find the relics of Lehman Brothers.

Look across New York at night and you can see a skyscraper, reaching up from the busy streets midtown.

These days, it has the name Barclays emblazoned across its top. Ten years ago, the sign said Lehman Brothers.

Lehman’s had been in business since 1850, slowly building up its business and its reputation.

By the early years of the 21st century, it was the fourth biggest investment bank in America, a global player.

By the end of 2008, it had gone – a bank that went bankrupt; the biggest corporate failure in history.

And when Lehman’s went down, so the American economy followed, and that led to a global financial crisis.

Lehman Brothers, that proud company, has become notorious as perhaps the most damaging corporate collapse in history.

A decade on, and the echoes of that failure reverberate through the States.

The shape of the housing market changed, the economy rollercoastered down, and then up, and society fractured.

If it hadn’t been for the financial crisis, we may never have got the undercurrent of discontent that led to both Brexit and President Trump.

On the back of all that, it is little wonder that Lehman’s former executives rarely speak in public – they, and their company, have become bywords for financial recklessness.

Dick Fuld, the chief executive, barely appeared in public for seven years after a bruising congressional session following the collapse.

Others have simply walked away from high-profile careers, and avoided the spotlight.

But now, one of the Lehman’s executives has spoken exclusively to Sky News.

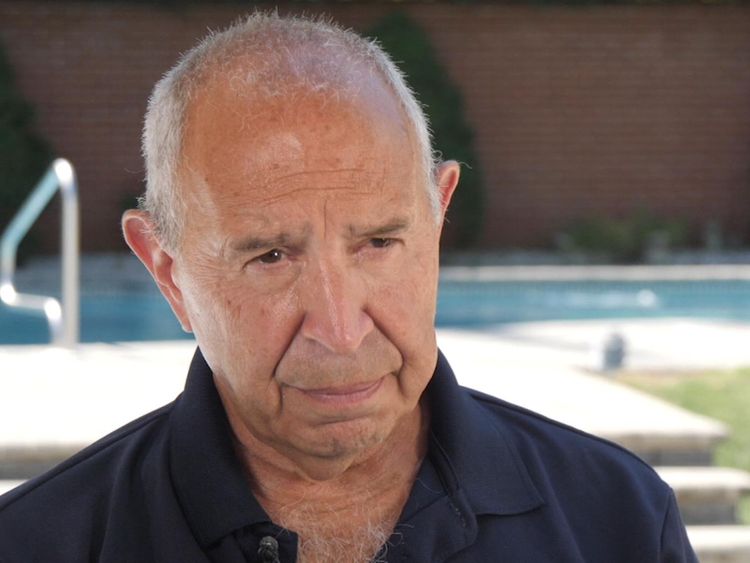

Tom Russo, who was Lehman’s managing director and chief legal officer when it filed for bankruptcy, says the bank was the “victim” of politics and should never have been allowed to collapse.

It is the first time he’s ever given an interview to a British journalist.

Mr Russo maintains that the US government, and in particular former treasury secretary Hank Paulson, made “a huge misjudgement” in not bailing out Lehman’s or helping the bank to restructure in its final days.

We met at his home in one of the wealthier suburbs of New Jersey.

He is a wealthy man, albeit one who lost millions of dollars in bonuses when Lehman’s collapsed.

He was there at the pivotal moments, a central voice in the hours when survival plans were made, and then rejected.

“We devised a way to split Lehman into a good bank, and a bad bank, so that we could put aside a lot of the assets that people were worried about,” he said.

“There were lots of discussions about to try to get people to buy parts of Lehman’s but fundamentally we ran out of time.

“Lehman’s was just doing what everybody else was doing. Everyone was leveraged with debt.

“The government aided and abetted it – they were the regulators of all these people.

“Lehman’s was a victim because they saved everyone else.

“They could have also let Goldman Sachs fail, or Morgan Stanley or Merrill Lynch or AIG. But they didn’t.

“They made a mistake with Lehman’s, they saw that mistake, and saved everyone else. There was a sort of mob mentality.”

Mr Russo said Mr Paulson did not want to be known as “Mister Bailout” but claims that, as the Lehman’s collapse was followed by a global economic panic, he rapidly realised the error of his ways – signing off massive deals to support other financial institutions.

Mr Russo said that has allowed the name of Lehman’s to be “tarred as being the cause when really the cause was so many other things – the consumer, the investment banks, the retail banks, the government, the ratings agencies…”

The financial crisis, he maintains, would have been “a lot less” savage if Lehman’s had been saved: “History has got Lehman’s dead wrong.”

Mr Russo was part of the executive team that tried, and failed, to save the bank.

Two years later, in a curious twist of fate, he was recruited by the Federal Reserve to join the leadership team of AIG, the insurance giant that was bailed out with around $200bn of government money and loaded with huge interest charges.

AIG eventually paid back more than $300bn, allowing Washington regulators to claim credit for making a profit on the bailout.

Mr Russo said the lesson for the future must be that governments should be more prepared to offer a “backstop” to troubled banks, something resisted by American politicians since the crisis.

When I suggested that the whole idea of protecting banks feels like a “moral hazard”, he simply shook his head: “It actually means you protect the people, it doesn’t mean you protect shareholders. You’re protecting the economy, not the company.”

“Moral hazard is a phrase thrown around, but it’s trumped by the danger to the economy,” he said.

“That was the flip from not saving Lehman’s to then saving everyone else. If we don’t learn from that, then we have learnt nothing from history.”

He is now retired. On his office wall, a poster decorated with good wishes from former colleagues at Lehman Brothers, including its chief executive, Mr Fuld.

They surround a copy of Mr Russo’s favourite poem, the Kipling classic, If.

Mr Russo refers to it often, not least the famous line that implores us to “meet triumph and disaster, and treat those two imposters just the same”.

He said the end of Lehman’s was the disaster of his career; his subsequent role in rejuvenating AIG was the triumph.

This is a man who has seen financial ruin at close hand.

He told me that those who worked through the 2008 crisis will never forget “the destruction and nervousness” that followed.

Now he worries that we are heading towards another crisis – one born of America’s vast mountain of debt.

The US government has an annual gross domestic product of $20tn, but a debt of more than $21tn. The debt is growing by around $1tn per year.

“We certainly are going to have another financial crisis, that’s just the way life is,” he said.

“My guess is that the seeds of it are certainly there today in leveraged debt. The debt is just going to keep growing.

“The laws of nature tell me that too much debt, versus your ability to pay it, is not a good thing.

“We keep on promising people things and don’t figure out how to pay for them.

“It’s hard to imagine the US running out of money – but in 2007, it was hard to imagine we were heading towards a crisis.”

From – SkyNews